The History of the Tibetan Language

Introduction

The Tibetan language, with its rich historical and cultural heritage, has been an integral part of the Tibetan Plateau’s identity for centuries. From its early oral traditions to the creation of a written script and its role in preserving Buddhist teachings, the history of the Tibetan language is a testament to the region’s intellectual and spiritual legacy. This essay traces the evolution of the Tibetan language, examining its origins, development, and enduring significance.

Origins and Early Development

The origins of the Tibetan language can be traced back to the early inhabitants of the Tibetan Plateau. The Tibetan language belongs to the Tibeto-Burman branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family, which includes a diverse array of languages spoken across East and Southeast Asia. Before the establishment of a written script, Tibetan was primarily an oral language, used by various tribes and communities for communication, trade, and cultural expression.

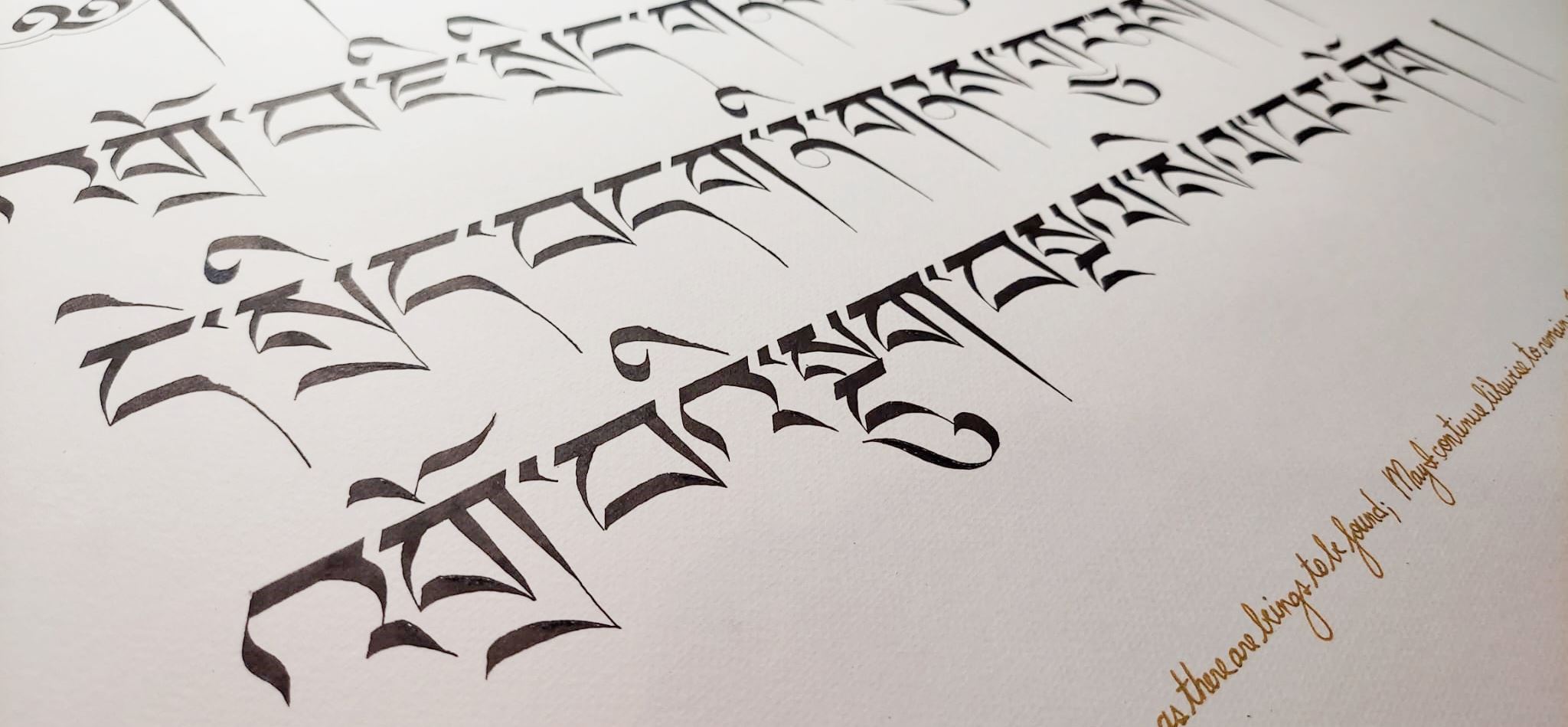

Creation of the Tibetan Script

The development of the Tibetan script is attributed to Thonmi Sambhota, a scholar sent by King Songtsen Gampo to India to study Sanskrit and the Indian writing systems. Upon his return, Thonmi Sambhota devised the Tibetan script, drawing inspiration from the Devanagari script used for Sanskrit. This new script consisted of thirty consonantal characters and four vowel diacritics, allowing for the accurate representation of Tibetan phonetics.

Thonmi Sambhota also composed several grammatical treatises, including the “Sumchupa” and “Rtags kyi ‘jug pa,” which laid the foundation for Tibetan grammar and orthography. These works provided the rules and guidelines for using the script, enabling the transcription of oral traditions, legal documents, and religious texts.

The Translation Movement and Buddhist Canon

The creation of the Tibetan script facilitated a monumental translation movement that profoundly influenced Tibetan culture and religion. With the advent of the written language, Tibetan scholars and monks embarked on an ambitious project to translate Buddhist scriptures from Sanskrit into Tibetan. This effort was not only linguistic but also an intellectual and spiritual endeavor, aiming to accurately convey the teachings of the Buddha in the Tibetan language.

The translation movement began in earnest during the reign of King Trisong Detsen (755–797 CE), who invited Indian Buddhist scholars, including the renowned Padmasambhava and Shantarakshita, to Tibet. These scholars worked alongside Tibetan translators to produce an extensive body of Buddhist literature, including the Kangyur (the translated words of the Buddha) and the Tengyur (the translated commentaries by Indian masters). These canonical texts remain central to Tibetan Buddhism and have been preserved and studied for centuries.

Classical Tibetan and Literary Flourishing

The translation movement and the establishment of Buddhist monasteries and educational institutions led to the flourishing of Classical Tibetan, the literary form of the language. Classical Tibetan became the standard for religious, scholarly, and administrative texts, and it remains the liturgical language of Tibetan Buddhism to this day.

During the height of the Tibetan Empire (7th to 9th centuries CE), Classical Tibetan was used to compose historical chronicles, legal codes, poetry, and philosophical treatises. The “Old Tibetan Annals” and the “Old Tibetan Chronicle” are among the earliest examples of Tibetan historical writing, providing valuable insights into the political and cultural developments of the period.

The Disintegration of the Tibetan Empire and the Era of Fragmentation

Following the collapse of the Tibetan Empire in the 9th century, Tibet entered a period of political fragmentation and regional division. Despite the political upheaval, the Tibetan language continued to evolve and adapt to the changing circumstances. Regional dialects emerged, reflecting the diverse linguistic landscape of the Tibetan Plateau.

During this era, the decentralization of political power led to the rise of local kingdoms and the establishment of monastic centers of learning. These monastic centers, such as Samye Monastery and Sakya Monastery, played a crucial role in preserving and disseminating Tibetan Buddhist teachings and literature. The monastic education system ensured the continuity of Classical Tibetan as the language of religious and scholarly discourse.

The Second Diffusion of Buddhism and the Renaissance of Tibetan Culture

The Second Diffusion of Buddhism (late 10th to early 12th centuries) marked a period of religious and cultural renaissance in Tibet. This era saw the revival of Buddhist teachings and the establishment of new monastic traditions, such as the Kadampa, Sakya, and Kagyu schools. These developments had a profound impact on the Tibetan language, leading to the production of an extensive body of religious and philosophical literature.

During this period, Tibetan scholars composed commentaries, philosophical treatises, and biographies of great Buddhist masters. The translation of new Buddhist texts from Sanskrit, Pali, and Chinese continued, enriching the Tibetan literary canon. Prominent figures such as Atisha, Marpa, and Milarepa made significant contributions to Tibetan religious literature, further solidifying the importance of the written language in the transmission of Buddhist teachings.

The Mongol Empire and the Rise of the Gelug School

The 13th century brought significant changes to Tibet with the rise of the Mongol Empire. The Mongols, under the leadership of Genghis Khan and his successors, established a vast empire that included Tibet. The relationship between Tibet and the Mongol Empire had a lasting impact on Tibetan politics, religion, and language.

One of the most influential developments during this period was the rise of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism, founded by Je Tsongkhapa (1357–1419). The Gelug school emphasized rigorous scholasticism and monastic discipline, leading to the establishment of major monastic universities such as Ganden, Sera, and Drepung. These institutions became centers of learning and played a crucial role in the preservation and dissemination of Classical Tibetan literature.

The support of the Mongol rulers facilitated the spread of the Gelug school and the establishment of the Dalai Lama institution. The Fifth Dalai Lama, Ngawang Lobsang Gyatso (1617–1682), further consolidated the political and religious authority of the Gelug school, leading to the creation of a unified Tibetan state. The Dalai Lama’s government promoted the use of Classical Tibetan as the language of administration, scholarship, and religion.

The Modern Period and Linguistic Challenges

The modern period brought new challenges and changes to the Tibetan language. The 20th century saw significant political upheaval, including the incorporation of Tibet into the People’s Republic of China in 1950. These events had a profound impact on Tibetan society, culture, and language.

In the aftermath of the Chinese takeover, many Tibetans, including the 14th Dalai Lama, fled into exile. The Tibetan diaspora, primarily based in India, Nepal, and Bhutan, has played a crucial role in preserving Tibetan culture and language. Tibetan exile communities have established schools, cultural centers, and monastic institutions dedicated to the preservation and promotion of the Tibetan language and heritage.

Within Tibet, the Chinese government’s policies towards the Tibetan language have been a source of controversy and concern. Efforts to promote Mandarin Chinese as the primary language of education and administration have raised fears about the erosion of Tibetan linguistic and cultural identity. Despite these challenges, Tibetan communities within Tibet and in exile continue to advocate for the preservation and revitalization of the Tibetan language.

Contemporary Efforts and the Future of the Tibetan Language

Contemporary efforts to preserve and promote the Tibetan language are multifaceted and involve both grassroots initiatives and institutional support. Tibetan language education is a key focus, with schools in exile communities offering instruction in Tibetan language and literature. The Tibetan Children’s Village (TCV) schools, established by the Tibetan exile community, provide comprehensive education in Tibetan language, culture, and history.

In addition to formal education, there are numerous initiatives aimed at promoting the Tibetan language through media, literature, and technology. Tibetan-language newspapers, radio stations, and television programs serve as important platforms for linguistic and cultural expression. The advent of digital technology has also opened up new possibilities for the preservation and dissemination of Tibetan language content, including online dictionaries, language learning apps, and digital archives of Tibetan texts.

The Tibetan language’s future depends on the continued commitment of Tibetan communities and the support of international organizations and governments. Efforts to document and study the diverse dialects of Tibetan, as well as the creation of comprehensive language resources, are essential for the preservation of the linguistic heritage. Collaborative projects involving Tibetan scholars, linguists, and cultural organizations are crucial for ensuring that the Tibetan language continues to thrive in the face of modern challenges.

Conclusion

The history of the Tibetan language is a testament to the resilience and creativity of the Tibetan people. From its early origins as an oral language to the creation of a written script and its role in preserving Buddhist teachings, the Tibetan language has been a cornerstone of Tibetan culture and identity. Despite the challenges posed by political upheaval and modernization, the Tibetan language continues to be a vibrant and essential part of Tibetan life.

The efforts to preserve and promote the Tibetan language reflect a deep commitment to maintaining the cultural and spiritual heritage of Tibet. As the Tibetan language evolves and adapts to new contexts, it remains a powerful symbol of the enduring legacy of Tibetan civilization. Through continued education, advocacy, and cultural expression, the Tibetan language will continue to be a vital part of the Tibetan people’s identity and heritage for generations to come.